Women make up the majority of the workforce in the community sector. They play a crucial role in improving the lives of other women, who also make up the bulk of people who use the services of community agencies.

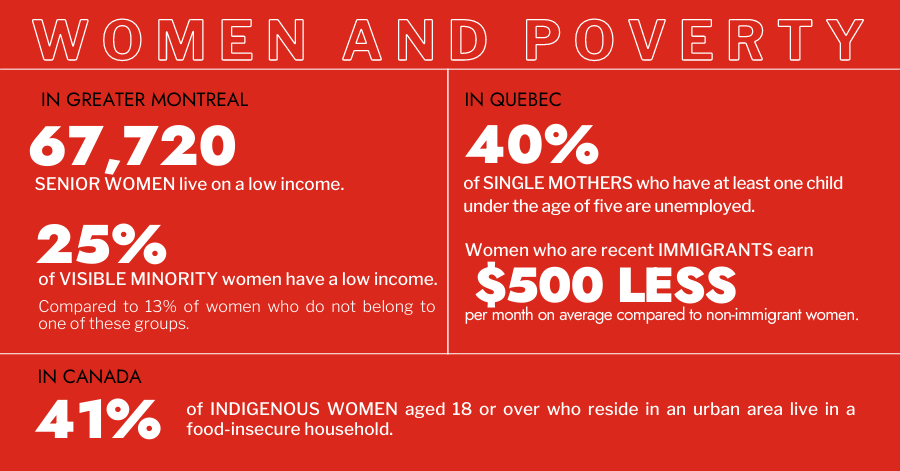

To mark International Women’s Day, we spoke to five community workers who help groups of women most at risk of poverty, such as single mothers, senior women, immigrant or racialized women, and Indigenous women.

Support for these women gives them greater independence, improves their living conditions, and even helps them leave violent environments.

Now is the time to give a voice to women who can raise other women up.

Valérie Larouche

Valérie Larouche has directed Mères avec pouvoir for almost 10 years. She is very familiar with the challenges faced by the young mothers at her agency, as she herself had to juggle the roles of single mother and student at one time.

In the past 20 years, Mères avec pouvoir has supported over 200 single mothers with their social, professional or housing goals. Although they all have unique stories, what do these 200 women have in common?

“They are under a lot of stress. Housing is a basic need. When you have a child, it’s so stressful not to have a place to live. These women are often in debt and have trouble meeting their food needs. Being stressed makes them less present for their child. Most have not completed high school and have low self-esteem. They are on their own too. They experience a lot of isolation and loneliness.

“Many have experienced forms of physical, psychological, emotional and even financial abuse. They haven’t always had time to mature before becoming mothers. Their network of friends can break down once their child comes. Some have to deal with their own parent being around all the time, while others are completely alone with their child with no emotional or material support from anyone.”

Some of these single mothers have had to wait a year or two before getting a spot at Mères avec pouvoir. Although in a vulnerable situation when they arrive, they are highly motivated to work on a life goal, such as going back to school or the job market.

“When they get here, the first thing they do is sign a commitment to themselves: I want to do X project, I need support to do Y goal, and this is how I’m going to achieve it. Going back to school is not just about getting up in the morning and going to class. It’s also about taking care of yourself, having a social network, making a budget, taking care of your home, making time to play with your child, and going to the doctor or pediatrician. It means having a life balance that gives you the space and motivation to meet your goal.”

Mères avec pouvoir supports women on their journeys, which can last from three to five years. The agency offers subsidized housing and a day care spot and provides individual support, activities, training, and workshops in a friendly and stimulating environment. At the end of their journeys, these women become photographers, nurses, educators, estheticians, or business owners, and they develop an invaluable support network.

“We don’t offer every service and instead connect women to resources in the neighbourhood. We don’t want their whole lives to revolve around Mères avec pouvoir because one day they’ll have to leave. Their transition is much easier when they have other footholds in the community. We make sure they have a support network and that both the mother and child have settled well into their neighbourhood.”

Mères avec pouvoir also provides off-site services to support single mothers who do not live at their centre.

“We don’t invite women who already have a unit in a co-op or HLM to move to our site, as this move is temporary. If they want support to find a day care spot, build a support network, or take action to meet a life goal, we can help them.”Mères avec pouvoir currently supports 30 single mothers on site and about 20 families off site. The agency will be rolling out a major campaign in the coming months to build a second 50-unit facility.

Manoucheka Céleste

Manoucheka Céleste is the founder and director of Mains Utiles. Originally from Haiti, she immigrated to Quebec in 2006 when she was 28 years old. A lawyer by training, she is also passionate about fashion, as she studied fashion design and then couture. With help from an advisor from the CDEC (community economic development corporation), she set up Main Utiles in 2013 to help immigrant women in Saint-Léonard.

“When you leave your home country and arrive in another one with a small suitcase and a few dollars in your pocket, you are automatically vulnerable. Immigrants have to take so many steps and make so many choices in their integration process, which generally lasts five years. Unfortunately, many women choose to focus on their family rather than join the work force. They often stay at home or take precarious part-time jobs and have to depend on their spouse. Fear can hold them back.”

Mains Utiles is for women who have not been able to fully develop their integration potential and who are experiencing isolation. The agency gives them the boost of courage they need to take charge of their lives. By attending sewing workshops to make clothes and other items, they develop a network of mutual support and become familiar with their host society.

“We give them a space to talk and share with other women. We want them to develop their independence and flourish in this society because, as I often say, there’s room for everyone. There is no need to be excluded, to be isolated, or to hide. Everyone can contribute.”

More than a sewing workshop, Mains Utiles is a whole community for immigrant women to which they develop a sense of belonging. They learn, discuss, talk, socialize, share with other women, and help each other.

With its solid roots in the community dynamics of Saint-Leonard, Mains Utiles mobilized in spring 2020 to deal with the unprecedented health crisis unfurling across the neighbourhood. Women at the sewing workshops made face masks that they distributed for free to people in the neighbourhood living in poverty and to children in schools.

With strict and recognized health precautions, Mains Utiles also took part in a cultural mediation project during the pandemic in which immigrant women were invited to write their past, present and future stories through a collective work.

“It was touching to see how these women opened their hearts to create this mural in an open, non-judgmental space. This project was really very important.” The mural is currently on display at the Saint-Leonard library. When health measures permit, Mains Utiles will tour the work to different neighbourhood agencies to be enjoyed by the community.

Diane Lévesque

Diane Lévesque is a staff member at the Carrefour d’information pour aînés of CATAL (Comité d’animation du troisième âge de Laval). Every year, this program meets the specific needs of about 50 seniors and runs on-site clinics to do the income taxes of over 225 people living at seniors’ residences, HLM or CHSLD.

Information hubs for seniors have been set up in most regions of Quebec. In Laval, CATAL is the centre responsible for helping seniors search for and understand government, municipal and community services. It isn’t easy to navigate the old age security pension, guaranteed income supplement, survivor allowance, housing allowance, and access to low-cost housing.

“Most women who seek our services are in poverty and not benefiting from all the programs they are entitled to. Also, 75% of them live alone. These women are over the age of 70 and, for the most part, have never worked. When they lose their spouse, they feel completely overwhelmed.”

CATAL looks high and low for every program and dollar that could benefit these senior women, and yet many remain in a vulnerable situation. During individual consultations, they identify other issues for these women and refer them to resources that can help.

In addition to poverty, the most common problems for seniors include psychological distress, anxiety, bereavement, isolation, cognitive impairment, mental and physical health problems, and caregiver fatigue.

“The seniors who some to us are generally referred by the CATAL community worker, community agencies, or the 211 phone line.

“At an individual consultation, we assess the person’s overall situation to find the best solutions to improve their living conditions. We help them understand and fill out forms, whether on paper or online. We also help them follow up with their requests, which can take a few months to get settled. They are invited to presentations that CATAL organizes about wills, leases, fraud, and financial abuse.”

In addition to its Carrefour d’information pour aînés, CATAL offers a range of services to Laval seniors in the areas of food security, caregiver respite, social and cognitive activities, adapted physical activities, community work, street outreach, etc.

Javiera Arroyo and Rachel Jordan

Javiera Arroyo and Rachel Jordan both work at the Women’s Centre of Montreal, the former as director of frontline services and the latter as a staff member in the Indigenous Women’s Support Program.

“There’s no doubt about it: despite being part of this country’s founding peoples, Indigenous women living off-reserve are among society’s poorest,” explains Javiera Arroyo.

Their life paths can be tortuous and full of obstacles from multiple problems, such as historical trauma, a loss of cultural roots and bearings, racism, discrimination, dependency, violence and poverty, among other factors.

“Most women who come to the Centre are in a situation of cyclical or hidden homelessness,” says Rachel Jordan. “Some go back and forth between their communities and the urban environment. Since they have no fixed address when they come to the city, they gravitate toward assistance resources and shelters. Some women have an apartment at an HLM or supervised housing, but these situations aren’t stable. They don’t have a lot of resources. While some are in relationships, most are single, separated or in the process of separating due to violence at home.

“These women were already in the system before coming to the city, as they were adopted or placed in foster care by the DPJ. Social and economic conditions are no better on the reserves. There are housing crises, people are very poor, and there are many social problems. There’s no future. Women often leave the reserve for a better future or for their safety because their lives depend on it. They sometimes come to the city ill-prepared for what lies ahead. They hope to rebuild their lives, but they come to a place with so many barriers.”

These barriers are what staff at the Women’s Centre of Montreal help them overcome by supporting them whenever hardship arises. Staff go with them to medical appointments or to court, make home visits, find emergency accommodation, or refer them to the right psychosocial or community resources. They give them a space to express their distress, talk about their abuse, or simply feel less isolated. They ensure that the rights of these Indigenous women are respected, that they are heard, and that they understand what is being explained to them.

“We provide a lot of individual services, but we want to resume our group activities, which have been very difficult to hold during the pandemic. We are setting up a room and a living environment where Indigenous women can meet to share their culture and break their isolation,” says Javiera Arroyo. “They can do beading or collective cooking activities and eat traditional dishes together.”

“For Indigenous women, for any Indigenous person, trauma healing comes through culture,” says Rachel Jordan. “Many of our women are survivors of residential schools or were placed with white families at a young age. They have lost contact with their culture and experienced multiple types of abuse. “The road to recovery is long, and every small step counts. People on the front lines don’t always see the fruit of their efforts, but they know they are planting small seeds. They do get news, as some women take the time to call about a new home, how they’ve gone back to school or work, or how they’ve returned to their community. “They tell us how wonderful it is. The important thing is that we are there for them on their journey, that we are part of their lives, and that they can count on us.”